Introduction

Tapeworm species include, but are not limited to, Taenia spp., Echinococcus spp., and Dipylidium caninum. This Vetpocket article is specific to Dipylidium caninum.

Dipylidium caninum is the most common tapeworm of dogs and cats.

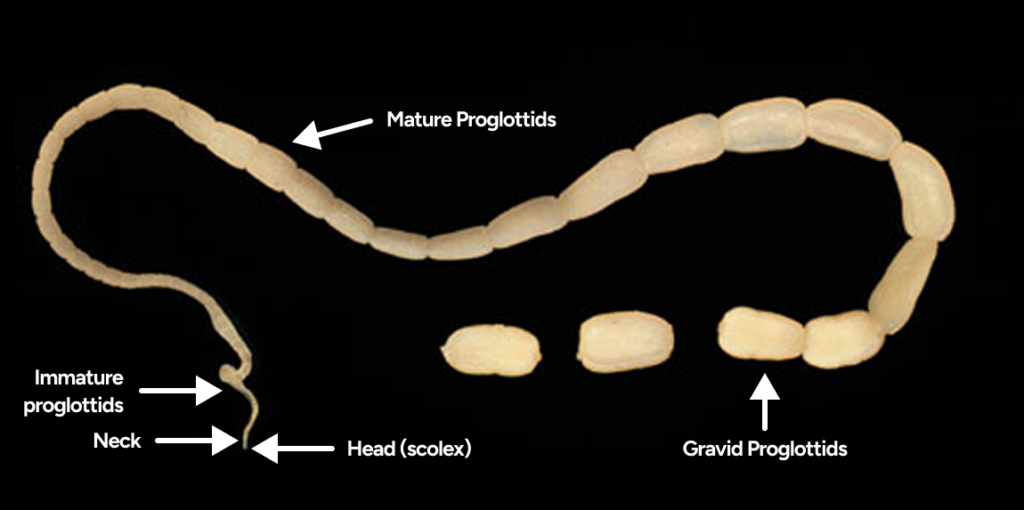

They are long, flat, segmented intestinal parasites, located within the small intestine of dogs and cats. Each segment (called a proglottid) is commonly described to have the appearance of a grain of rice.

For Dipylidium caninum to be infectious in dogs or cats, it has to first pass through an intermediate host: the dog or cat flea (Ctenocephalides spp.), or less frequently through the dog louse (Trichodectes canis). The reason an intermediate host is required is for completion of the tapeworm life cycle. Dipylidium caninum is therefore commonly referred to as the “flea tapeworm” of dogs and cats.

Taxonomy

Domain: Eukarya

Kingdom: Animalia (animals)

Phylum: Platyhelminthes (flatworms)

Class: Cestoda (tapeworms)

Order: Cyclophyllidea

Family: Dipylidiidae (formerly Diplepidedae)

Genus: Dipylidium

Species: Dipylidium caninum

Common Names

Some common names include “flea tapeworm”, “cucumber seed tapeworm”, and “double-pored tapeworm”.

Geographic Distribution

Can be found worldwide.

Hosts

Definitive hosts are canids, felids, and rarely humans.

Intermediate hosts are the dog or cat flea (Ctenocephalides spp.), and less frequently the dog louse (Trichodectes canis).

Prepatent Period

~2 to 3 weeks; which means that the definitive host may start shedding proglottids as early as ~2 to 3 weeks following infection.

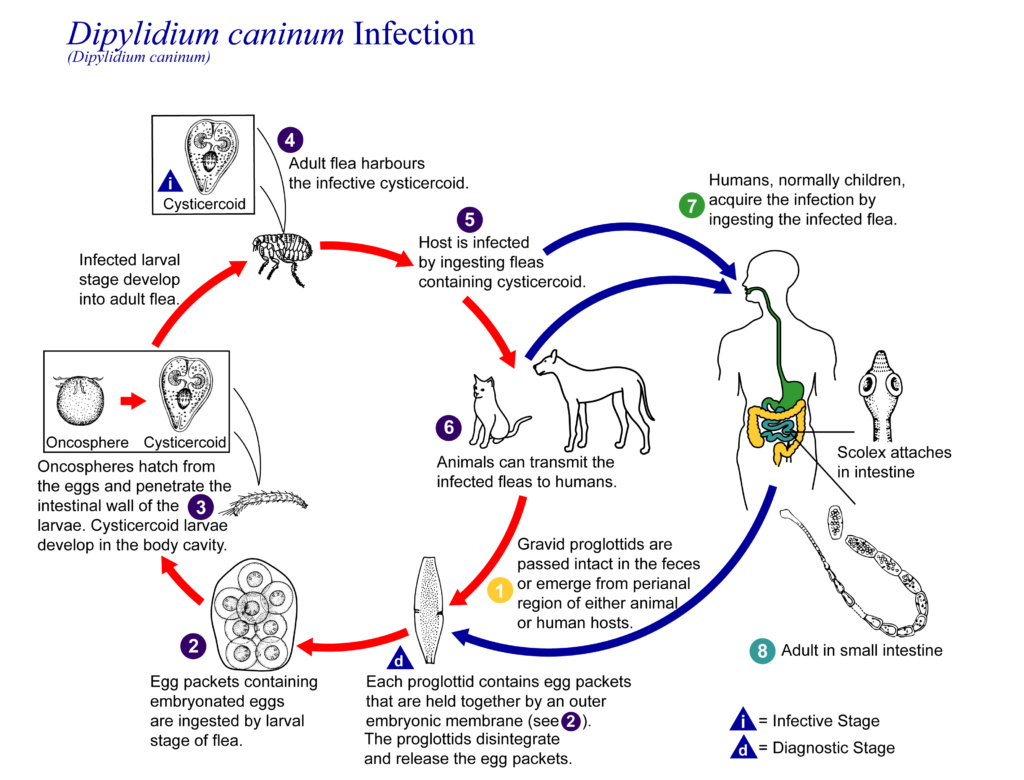

Life Cycle

Indirect life cycle (multiple hosts: definitive and intermediate hosts).

A dog or cat ingests an adult dog or cat flea (or less frequently, an adult dog louse) that is infected with cysticercoids (tapeworm larvae). This occurs most commonly when dogs or cats groom themselves, particularly when excessively licking or chewing their skin as a result of having a flea infestation.

The cysticercoids are released in the small intestine of the dog or cat, and then develop into adult tapeworms.

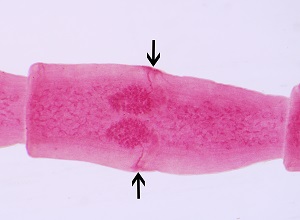

The tapeworm head attaches to the small intestinal wall of the dog or cat.

New proglottids form at the neck of the tapeworm, and older proglottids are pushed toward the posterior (tail) of the tapeworm.

The posterior proglottids at the end of the tail are filled with egg packets.

These egg-filled posterior proglottids (also called gravid proglottids) detach and migrate to the perianal region of the dog or cat, or pass in the dog or cat’s feces and into the environment.

The gravid proglottids dry out and disintegrate, releasing their egg packets into the environment.

A dog or cat flea (or dog louse) larva ingests an egg packet from the environment. Each egg packet is filled with multiple eggs.

These ingested eggs then release their oncospheres (tapeworm embryos) in the dog or cat flea’s (or dog louse’s) intestine which then develop into cysticercoids as the dog or cat flea (or dog louse) larva matures into an adult dog or cat flea (or adult dog louse).

The adult dog or cat flea (or adult dog louse) harbors the infective cysticercoids.

Clinical Signs

Infection is commonly asymptomatic (has no clinical signs).

If there are clinical signs, clinical signs can include:

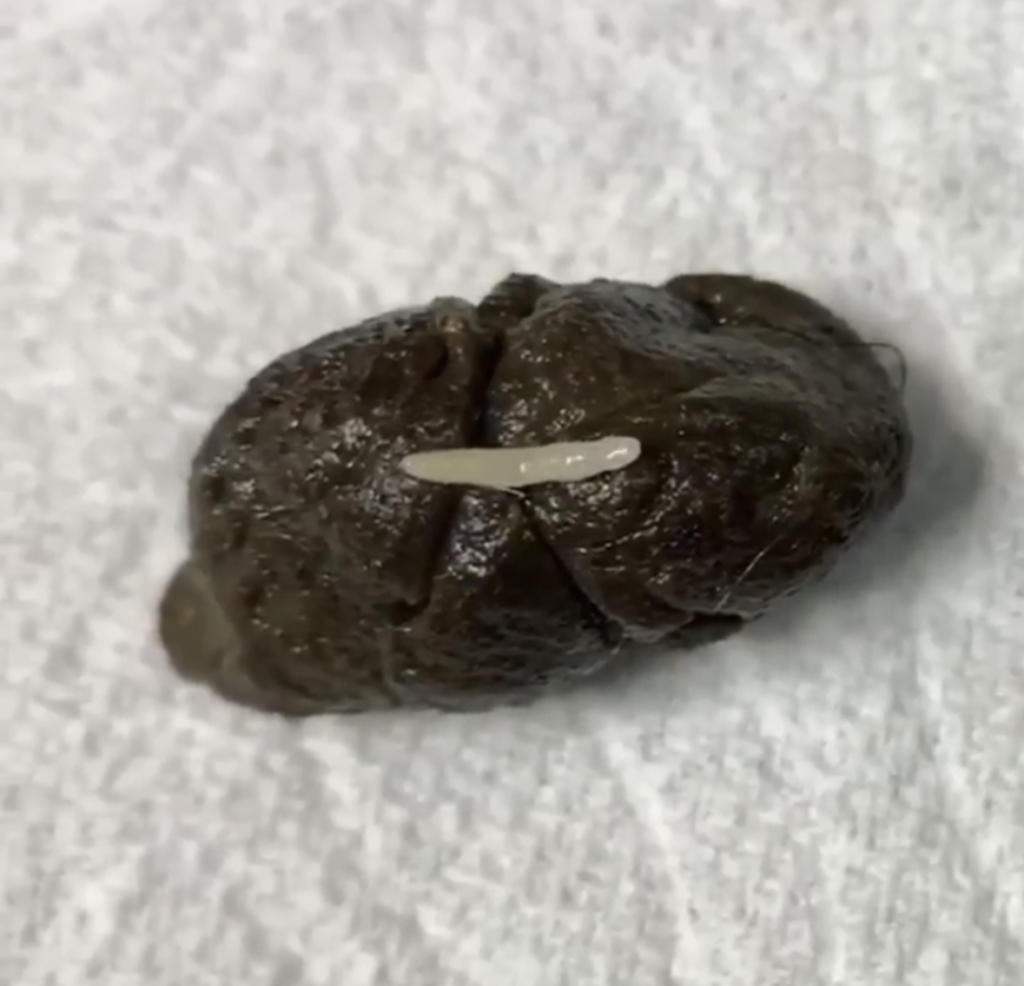

- motile or dried white to gold colored proglottid (“rice grain”, “cucumber seed”, or “sesame seed”) in the perianal and/or perineal regions

- motile or dried white to gold colored proglottid (“rice grain”, “cucumber seed”, or “sesame seed”) in the feces

- motile or dried white to gold colored proglottid (“rice grain”, “cucumber seed”, or “sesame seed”) in the patient’s environment (e.g. bedding, carpet, furniture)

- perianal and/or perineal irritation and pruritus, which commonly presents as excessive grooming and/or dragging of those regions across the ground (“scooting”), and is due to the proglottids getting stuck to the fur in those regions

- heavy infestation can cause diarrhea, weight loss, failure to thrive, poor coat, abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction, and/or vomiting

- migration to the stomach can occasionally occur, which could result in the dog or cat vomiting an adult tapeworm several inches long

Diagnosis

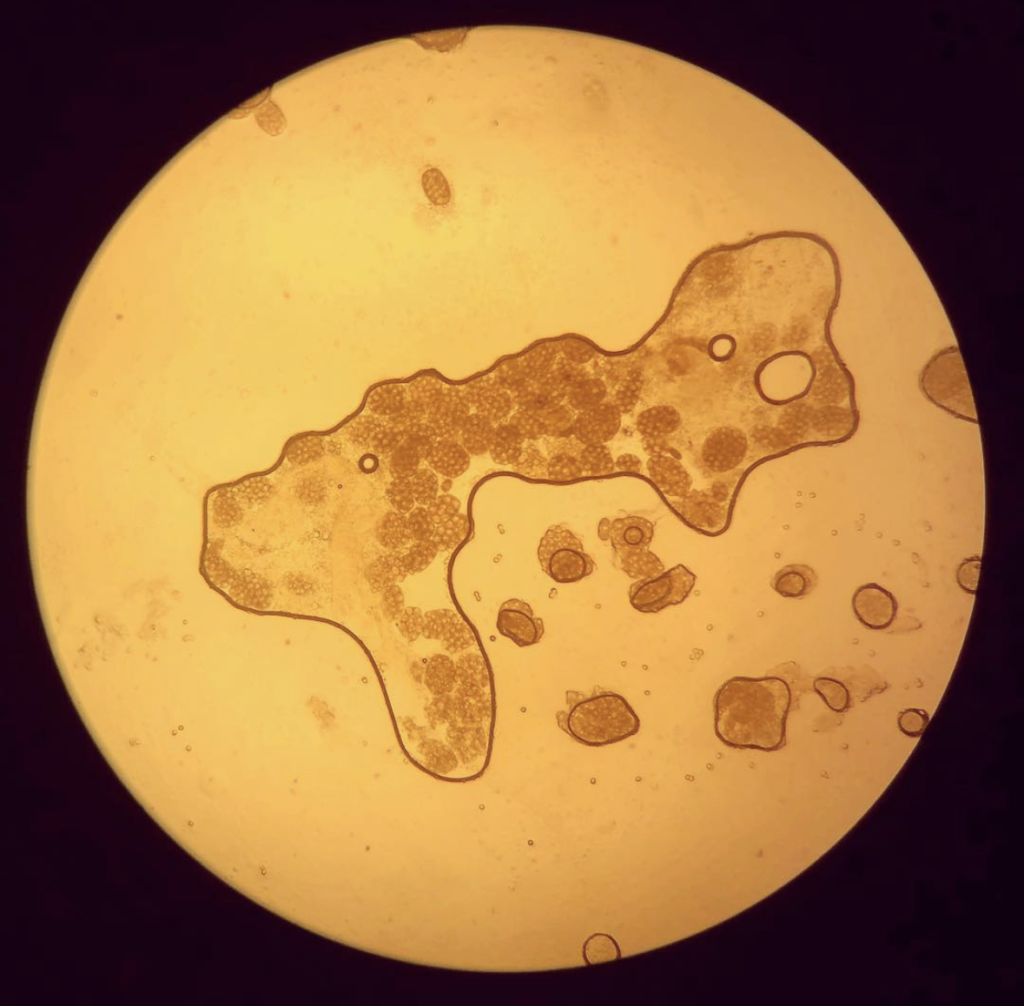

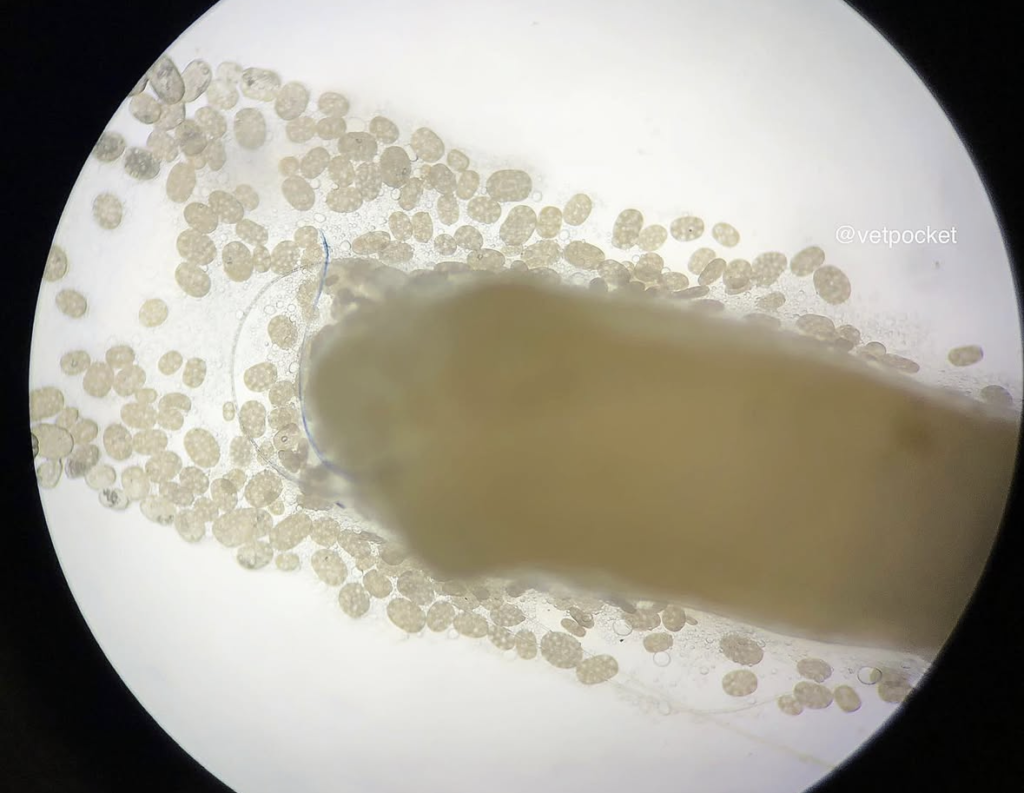

Adult tapeworms are ~15 to 70 cm in length, and consist of a head segment (scolex), a neck segment, and a body (strobila) made up of multiple segments (proglottids). Each proglottid is oblong and roughly the size of a grain of rice, ~10 to 12 mm in length, and contain bilateral genital pores. Each egg packet is round to ovoid, ~120 to 200 mcm in length, and contains ~2 to 63 (average is ~25 to 30) individual eggs. Individual eggs are round to oval, pale yellow, ~35 to 60 mcm in diameter, and contain an oncosphere that has 6 hooklets (hexacanth embryo).

Diagnosis is commonly preliminarily made based on clinical signs including identifying the proglottids in the perianal and/or perineal regions, in the feces, and/or in the patient’s environment.

(i) Freshly passed proglottids are white, moist, soft, motile, and look like cooked grains of white rice or cucumber seeds that are crawling.

(ii) Dried proglottids are hard, golden in color, non-motile, and look like sesame seeds.

(iii) Microscopic exam of an intact proglottid placed on a slide, and seeing if the proglottid is releasing its egg packets (like a chicken laying eggs).

(iv) Microscopic exam of a proglottid (with or without a few drops of water or saline) crushed between a slide and a cover slip to see if egg packets are appreciated.

(v) Fecal antigen.

(vi) Fecal PCR.

(vii) Fecal flotation for egg identification – but due to inconsistent floating of the tapeworm egg, Dipylidium caninum infections are rarely diagnosed on fecal flotation, and are more commonly diagnosed based on one of the above methods.

Treatment Options

Check all dosing recommendations. Some are off-label. Check drug formularies for all cautions, contraindications, etc.

Recommendations include one of the following:

- Praziquantel 5 mg/kg PO or SC once in dogs and cats. Do not use in puppies < 4 weeks of age or kittens < 6 weeks of age.

- Epsiprantel 5.5 mg/kg PO once in dogs and 2.75 mg/kg PO once in cats. Do not use in patients < 4 weeks of age.

- A combination product consisting of febantel 25 mg/kg + pyrantel pamoate 5 mg/kg + praziquantel 5 mg/kg PO once in dogs. Do not use in puppies < 3 weeks of age or < 2 lb in weight.

Only a single treatment with one of the above anthelmintic medications is required. Sometimes, however, a repeat treatment in approximately 3 weeks is recommended, most notably when there is a significant flea infestation due to the risk of patient reinfection by ingesting another cysticercoid infected adult flea.

Part of the treatment protocol should include flea control (or louse treatment). The patient and all pets in the household should be placed on a good quality monthly flea prevention, as well as treating the environment (e.g. frequent vacuuming and emptying the contents outside in the garbage, commercial flea treatment products for the home).

Monitor for proglottids following treatment.

Prevention

Prevention consists of keeping dogs and cats on good quality monthly flea prevention, as well as controlling lice.

The environment also needs to be controlled. Other animals (e.g. rodents, rabbits, coyotes, wolves, foxes) are capable of bringing the sources of infection (e.g. fleas) into the dog or cat’s environment.

Zoonosis and/or Contagious Potential

Dipylidium caninum has zoonotic potential, but not directly from a dog or cat, instead, a human must ingest a cysticercoid infected adult flea or louse for infection to occur, making risk of infection in humans low.

Similarly with dogs and cats, dogs and cats must ingest a cysticercoid infected adult flea or louse for infection to occur.

Prognosis

Dipylidium caninum infections are typically simple and easy to treat, with an excellent prognosis once successfully treated.

References

CAPC (Companion Animal Parasite Council) Guidelines 2024. Asscessed February 4, 2026. https://capcvet.org/guidelines/dipylidium-caninum/

Zajac A and Conboy G. Veterinary Clinical Parasitology, Seventh Edition, Blackwell Publishing, 2006

Ettinger S, Feldman E, Cote E. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 8th Edition, Elsevier, 2017

Dutch Caribbean Species Register website. Accessed February 4, 2026. https://www.dutchcaribbeanspecies.org/linnaeus_ng/app/views/species/nsr_taxon.php?id=192527&cat=CTAB_NAMES

CDC website. Accessed February 4, 2026. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/dipylidium/index.html

Western College of Veterinary Medicine website. Accessed February 4, 2026. https://wcvm.usask.ca/learnaboutparasites/parasites/dipylidium-caninum.php

Elanco website. Accessed February 4, 2026. https://yourpetandyou.elanco.com/us/our-products/drontal-plus-for-dogs

FDA website. Accessed February 4, 2026. https://animaldrugsatfda.fda.gov/adafda/app/search/public/document/downloadFoi/557

Dr. Danelia de Kock’s Veterinary School Notes

Disclaimer

This information is not intended to replace clinical judgment or guide individual care in any matter. Please check any information and values prior to use and use at your own risk.

Reference to specific commercial products, manufacturers, companies, or trademarks does not constitute its endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC images and photos used in this article are available on their website for no charge.